Day 11 — Kernel Density Estimation: Smoothing Out the Bumps

Every data point tells a story; KDE weaves them into a smooth narrative.

Kernel Density Estimation creates smooth distributions by placing a kernel at each data point and summing them together.

Note: This article uses technical terms and abbreviations. For definitions, check out the Key Terms & Glossary page.

The Histogram Problem: Too Blocky, Too Sensitive

Imagine you're analyzing the heights of 100 people. You create a histogram:

Show code (9 lines)

Count

8

6

4

2

→ Height

5'0" 5'4" 5'8" 6'0" 6'4"

Problems:

- Blocky - Real height distribution is smooth, not stepwise

- Bin-dependent - Move bins by 2 inches, get a completely different picture!

- Hard to compare - Overlay two histograms? Messy!

Enter Kernel Density Estimation (KDE): The smooth, elegant solution.

The Big Idea: Every Point is a Little Hill

Instead of dropping data into bins, KDE says:

"Let's place a small, smooth hill (kernel) at each data point, then add them all up!"

Visual Intuition

Data points: [2, 3, 5, 8, 9]

Step 1: Place a "bell curve" at each point

Density

→ Value

2 3 5 8 9

Step 2: Add them all together

Density

→ Value

2 3 5 8 9

Result: A smooth, continuous density curve!

The Math: Kernels and Bandwidth

The KDE Formula

For data points x₁, x₂, ..., xₙ, the density at any point x is:

f̂(x) = (1/n) Σᵢ₌₁ⁿ K((x - xᵢ)/h)

Breaking it down:

- f̂(x) = estimated density at point x

- n = number of data points

- K(·) = kernel function (usually Gaussian/normal curve)

- xᵢ = the i-th data point

- h = bandwidth (controls width of each hill)

- (x - xᵢ)/h = how far x is from xᵢ, scaled by bandwidth

The Gaussian Kernel (Most Common)

K(u) = (1/√(2π)) × exp(-u²/2)

This is just a standard normal distribution!

In full:

f̂(x) = (1/(n×h×√(2π))) × Σᵢ₌₁ⁿ exp(-(x - xᵢ)²/(2h²))

Translation: Place a normal curve with standard deviation h at each data point, add them up, normalize by n.

Other Kernel Options

While Gaussian is most popular, you can use different "hill shapes":

Epanechnikov (most efficient):

K(u) = (3/4)(1 - u²) if |u| ≤ 1, else 0

Shape: (parabolic hump)

Uniform (box):

K(u) = 1/2 if |u| ≤ 1, else 0

Shape: (flat top)

Triangular:

K(u) = 1 - |u| if |u| ≤ 1, else 0

Shape: /\ (triangle)

Good news: Kernel choice matters much less than bandwidth choice! Usually just stick with Gaussian.

The Critical Choice: Bandwidth (h)

Bandwidth is the most important parameter in KDE. It controls how smooth your curve is.

Small Bandwidth (Undersmoothing)

Show code (9 lines)

h = 0.1 (very small)

Density

→ Value

Too wiggly! Shows every tiny bump.

Might be capturing noise, not signal.

Problems:

- High variance (changes a lot with different samples)

- Overfitting (capturing random fluctuations)

- Hard to see the overall pattern

Large Bandwidth (Oversmoothing)

Show code (9 lines)

h = 5.0 (very large)

Density

→ Value

Too smooth! Hides important features.

Might miss real peaks.

Problems:

- High bias (systematic error)

- Underfitting (missing real structure)

- Might hide multimodality (multiple peaks)

Just Right Bandwidth

Show code (9 lines)

h = 0.5 (just right)

Density

→ Value

Smooth enough to see the pattern,

detailed enough to catch real features!

The Bias-Variance Tradeoff

This is one of the most fundamental concepts in statistics and machine learning!

Mathematical Formulation

Mean Squared Error (MSE) at point x:

MSE(x) = E[(f̂(x) - f(x))²]

= Bias²(x) + Variance(x)

Where:

- f̂(x) = our KDE estimate

- f(x) = true (unknown) density

- E[·] = expected value (average over many samples)

Bias:

Bias(x) = E[f̂(x)] - f(x)

Systematic error from smoothing

Variance:

Variance(x) = E[(f̂(x) - E[f̂(x)])²]

Random error from finite sample

The Bandwidth Effect

Small h:

- Low bias (follows data closely)

- High variance (jumps around with different samples)

- Result: Overfit - looks great on this sample, terrible on new data

Large h:

- High bias (oversmooths, misses features)

- Low variance (stable across samples)

- Result: Underfit - consistent but systematically wrong

Optimal h:

- Balances both

- Minimizes total MSE

Visual Representation

Show code (11 lines)

Error

Total MSE

Bias²

______ Variance

→ Bandwidth (h)

small optimal large

Silverman's Rule of Thumb

How do we choose h? Silverman's rule gives us a data-driven default:

h = 0.9 × min(σ, IQR/1.34) × n^(-1/5)

Breaking it down:

σ = standard deviation of data

IQR = interquartile range (Q₃ - Q₁)

n = sample size

min(σ, IQR/1.34) = robust estimate of spread (protects against outliers)

n^(-1/5) = sample size adjustment (more data → smaller bandwidth)

Why This Formula?

The IQR/1.34 part:

For normal distribution, IQR ≈ 1.34σ. Using min(σ, IQR/1.34) gives us:

- σ if data is normal

- IQR/1.34 if data has outliers (more robust!)

The n^(-1/5) part:

Comes from minimizing asymptotic MSE. As sample size grows:

- n = 100 → n^(-1/5) = 0.398

- n = 1000 → n^(-1/5) = 0.251

- n = 10000 → n^(-1/5) = 0.158

More data → tighter bandwidth (can afford more detail)

The 0.9 constant:

Empirically tuned for Gaussian kernels to work well in practice.

Example Calculation

Data: [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] (n=10)

Show code (10 lines)

Mean = 9.5

σ = √[(Σ(xᵢ - 9.5)²)/10] = 2.87

Q₁ = 6.75, Q₃ = 12.25

IQR = 12.25 - 6.75 = 5.5

IQR/1.34 = 4.10

min(2.87, 4.10) = 2.87

h = 0.9 × 2.87 × 10^(-1/5)

= 0.9 × 2.87 × 0.631

= 1.63

Bandwidth ≈ 1.63

Alternative Bandwidth Selection Methods

Scott's Rule

h = σ × n^(-1/(d+4))

Where d = number of dimensions (usually 1 for univariate KDE)

For 1D: h = σ × n^(-1/5) (simpler than Silverman!)

Plug-in Methods

Use calculus to estimate optimal h based on second derivative of true density (computationally intensive but more accurate)

Cross-Validation

Try many h values, pick the one that best predicts held-out data (most accurate but slowest)

In practice: Silverman's rule works great 90% of the time!

Comparing Groups: The Power of Overlaid KDEs

This is where KDE really shines! Let's compare "Effective" vs "Non-Effective" treatments.

The Data

Effective Group: [65, 70, 72, 75, 78, 80, 82, 85, 87, 90]

Non-Effective Group: [45, 48, 50, 52, 55, 58, 60, 62, 65, 68]

Histogram Comparison (Messy)

Count

→ Value

40 60 80 100

= Non-Effective

= Effective

Hard to compare! Bins don't align, overlaps confusing.

KDE Comparison (Beautiful)

Density

→ Value

40 60 80 100

Non-Effective (shifted left)

Effective (shifted right)

Insights instantly visible:

- Effective group centered ~15 points higher

- Similar spread (variance)

- Both roughly normal

- Minimal overlap (~10%)

Exercise: How Bandwidth Hides Multimodality

Let's explore a dataset with TWO distinct groups that we want to discover.

The Data: Hidden Bimodal Distribution

Data: [10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]

Two clear clusters: one around 12, one around 52.

Small Bandwidth (h = 1.0) - Truth Revealed

Density

________

→ Value

10 20 30 40 50 60

Two peaks clearly visible! This is bimodal data.

Calculation at x = 12 (first peak):

Show code (11 lines)

f̂(12) = (1/(12×1×√(2π))) × [

exp(-(12-10)²/2) +

exp(-(12-11)²/2) +

exp(-(12-12)²/2) + ← Highest contribution

exp(-(12-13)²/2) +

exp(-(12-14)²/2) +

exp(-(12-15)²/2) +

exp(-(12-50)²/2) + ← Near zero

... (far points contribute ~0)

]

Medium Bandwidth (h = 5.0) - Hints of Structure

Density

____

→ Value

10 20 30 40 50 60

Still see two bumps, but the valley between is shallower. Starting to blur together.

Large Bandwidth (h = 15.0) - Truth Hidden!

Density

→ Value

10 20 30 40 50 60

One smooth hump! The bimodality is completely hidden.

You'd conclude this is unimodal (one group) when it's actually two distinct populations!

Very Large Bandwidth (h = 30.0) - Maximum Blur

Density

→ Value

10 20 30 40 50 60

So smooth it's nearly flat! All information lost.

The Lesson: Bandwidth is Critical!

Too small: See noise as signal (false peaks)

Too large: Miss real structure (hidden modes)

Just right: Reveal true patterns

Pro tip: Always try multiple bandwidths when exploring new data! Start with Silverman's rule, then explore ±50%.

Practical Implementation

Python with scipy

Show code (32 lines)

from scipy.stats import gaussian_kde

import numpy as np

# Your data

effective = [65, 70, 72, 75, 78, 80, 82, 85, 87, 90]

non_effective = [45, 48, 50, 52, 55, 58, 60, 62, 65, 68]

# Create KDE objects (uses Silverman's rule by default)

kde_eff = gaussian_kde(effective)

kde_non = gaussian_kde(non_effective)

# Or specify bandwidth manually

kde_eff = gaussian_kde(effective, bw_method=0.5) # h = 0.5

# Evaluate on a grid

x_grid = np.linspace(40, 100, 1000)

density_eff = kde_eff(x_grid)

density_non = kde_non(x_grid)

# Plot

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.plot(x_grid, density_eff, label='Effective', color='green')

plt.plot(x_grid, density_non, label='Non-Effective', color='red')

plt.fill_between(x_grid, density_eff, alpha=0.3, color='green')

plt.fill_between(x_grid, density_non, alpha=0.3, color='red')

plt.xlabel('Value')

plt.ylabel('Density')

plt.legend()

plt.title('KDE Comparison: Effective vs Non-Effective')

plt.show()

Adjusting Bandwidth

Show code (15 lines)

# Silverman's rule (default)

kde = gaussian_kde(data)

# Manual bandwidth

kde = gaussian_kde(data, bw_method=1.5)

# Scott's rule

kde = gaussian_kde(data, bw_method='scott')

# Custom function

def my_bandwidth(kde_object):

return 0.5 * kde_object.scotts_factor()

kde = gaussian_kde(data, bw_method=my_bandwidth)

Tie-Back: get_density_plots in Our Toolkit

Show code (48 lines)

def get_density_plots(effective_data, non_effective_data,

bandwidth='silverman'):

"""

Visualize density shifts between two groups

Parameters:

- effective_data: Array of values for effective group

- non_effective_data: Array for non-effective group

- bandwidth: 'silverman', 'scott', or float value

Returns: matplotlib figure showing overlaid KDEs

"""

# Create KDE for each group

kde_eff = gaussian_kde(effective_data, bw_method=bandwidth)

kde_non = gaussian_kde(non_effective_data, bw_method=bandwidth)

# Create evaluation grid

all_data = np.concatenate([effective_data, non_effective_data])

x_min, x_max = all_data.min(), all_data.max()

padding = (x_max - x_min) * 0.1

x_grid = np.linspace(x_min - padding, x_max + padding, 1000)

# Evaluate densities

dens_eff = kde_eff(x_grid)

dens_non = kde_non(x_grid)

# Plot with fills

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 6))

ax.plot(x_grid, dens_eff, 'g-', linewidth=2, label='Effective')

ax.plot(x_grid, dens_non, 'r-', linewidth=2, label='Non-Effective')

ax.fill_between(x_grid, dens_eff, alpha=0.3, color='green')

ax.fill_between(x_grid, dens_non, alpha=0.3, color='red')

# Add rug plots (individual data points)

ax.plot(effective_data, np.zeros_like(effective_data),

'g|', markersize=10, alpha=0.5)

ax.plot(non_effective_data, np.zeros_like(non_effective_data),

'r|', markersize=10, alpha=0.5)

ax.set_xlabel('Value', fontsize=12)

ax.set_ylabel('Density', fontsize=12)

ax.set_title('Density Comparison: Treatment Effectiveness',

fontsize=14)

ax.legend()

ax.grid(alpha=0.3)

return fig

Use case: Medical trial data, A/B test results, before/after comparisons. Anywhere you need to see if distributions differ!

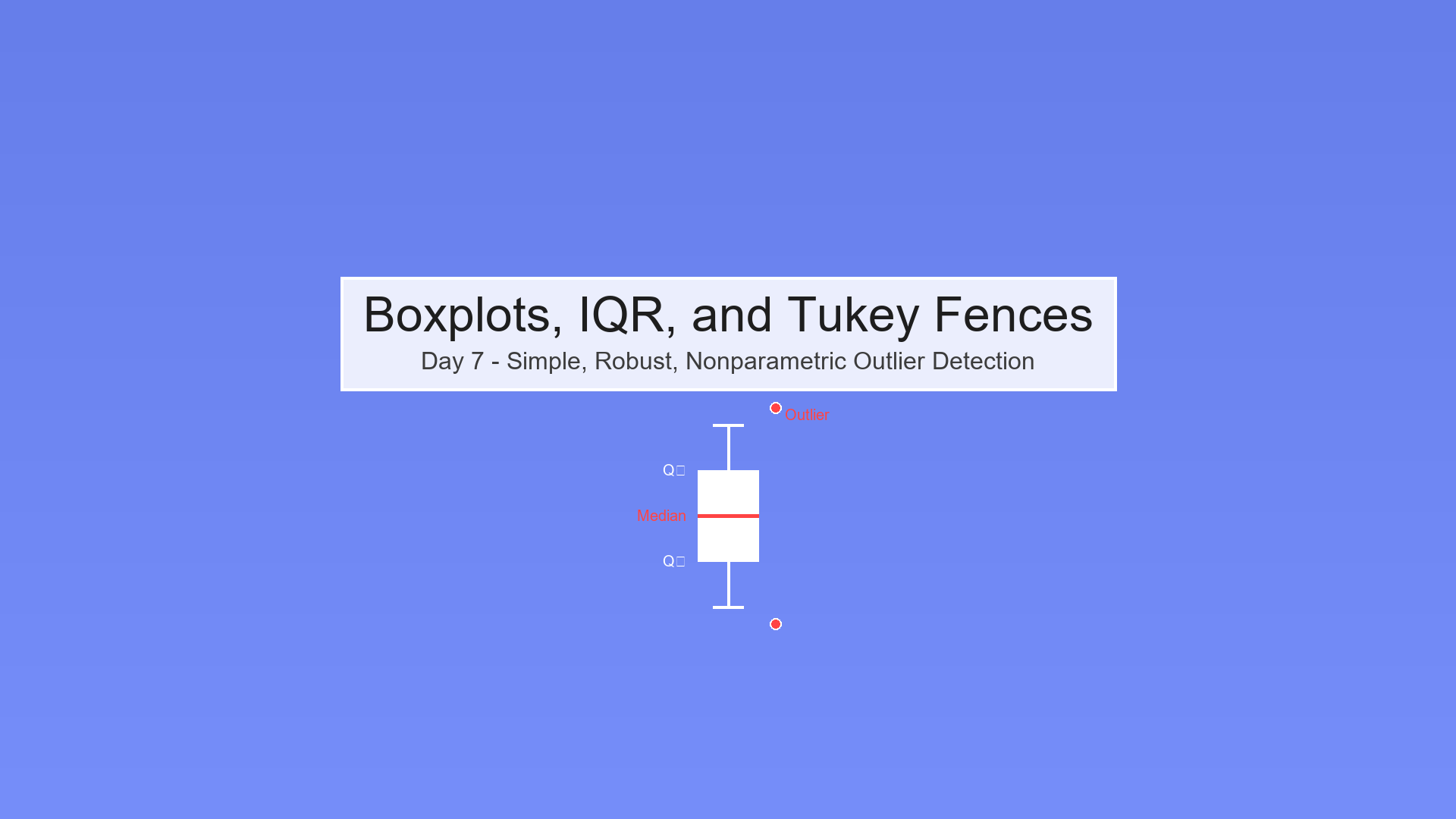

When to Use KDE vs Other Methods

Use KDE When:

Comparing distributions between groups

Need smooth, publication-quality plots

Exploring data shape (uni/bimodal, skewed, etc.)

Sample size is moderate to large (n > 30)

Want to estimate probability at any point

Use Histograms When:

Very large datasets (millions of points)

Need exact counts

Discrete data (coin flips, dice rolls)

Presenting to audiences unfamiliar with KDE

Use Box Plots When:

Want to highlight outliers specifically

Comparing many groups (5+)

Focus on quartiles, not full distribution shape

Don't Use KDE When:

Very small samples (n < 20) - too unreliable

Heavy outliers that might dominate bandwidth selection

Discrete data with few categories (use bar charts)

Advanced Topics

Multivariate KDE

KDE extends to 2D, 3D, etc.:

f̂(x, y) = (1/(n×h₁×h₂)) × Σᵢ K((x-xᵢ)/h₁, (y-yᵢ)/h₂)

Useful for visualizing 2D point clouds with contours!

Adaptive Bandwidth

Use different h for different regions:

- Narrow bandwidth where data is dense

- Wide bandwidth where data is sparse

More complex but can reveal local structure better.

Boundary Correction

KDE at edges (min/max of data) can be biased because the kernel "spills over" the boundary. Solutions:

- Reflection method

- Boundary kernels

- Truncation

Common Pitfalls

- Using default bandwidth blindly

- Always check! Plot with several h values

- Interpreting density as probability

- Density at x ≠ P(X = x)

- Probability requires integrating: P(a < X < b) = ∫ₐᵇ f̂(x)dx

- Comparing groups with different bandwidths

- Use same h for both groups or comparison is unfair!

- Over-interpreting small sample KDE

- n = 10? That KDE is very uncertain!

- Ignoring multimodality

- If you see multiple peaks, investigate! Could be important subgroups

Summary

Kernel Density Estimation transforms discrete data into smooth, continuous distributions:

Key Concepts:

KDE formula: f̂(x) = (1/nh) Σ K((x-xᵢ)/h)

Bandwidth h is critical - controls smoothness

Bias-variance tradeoff: small h (wiggly), large h (oversmoothed)

Silverman's rule: h = 0.9 × min(σ, IQR/1.34) × n^(-1/5)

Gaussian kernel most common: K(u) = exp(-u²/2)/√(2π)

Perfect for comparing groups - overlaid curves show shifts clearly

Watch for hidden modes - too much smoothing hides structure

The Beautiful Tradeoff:

Small bandwidth → See everything (including noise)

Large bandwidth → See nothing (smooth blur)

Optimal bandwidth → See truth (signal without noise)

Practical Wisdom:

Start with Silverman, explore ±50%

Always visualize with multiple bandwidths

Look for multimodality - it might be real!

Use color/fill for group comparisons

Report your bandwidth choice (reproducibility!)

Takeaway

Kernel Density Estimation gives you smooth, publication-ready visualizations that reveal the true shape of your data. Master bandwidth selection, understand the bias-variance tradeoff, and you'll have a powerful tool for comparing groups and exploring distributions. When histograms feel too blocky and box plots too summary, KDE is your elegant solution.

References

-

Silverman, B. W. (1986). Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

-

Scott, D. W. (1992). Multivariate Density Estimation: Theory, Practice, and Visualization. John Wiley & Sons.

-

Wand, M. P., & Jones, M. C. (1995). Kernel Smoothing. Chapman and Hall/CRC.

-

Sheather, S. J., & Jones, M. C. (1991). A reliable data-based bandwidth selection method for kernel density estimation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 53(3), 683–690.

-

Epanechnikov, V. A. (1969). Non-parametric estimation of a multivariate probability density. Theory of Probability & Its Applications, 14(1), 153–158.

-

Rosenblatt, M. (1956). Remarks on some nonparametric estimates of a density function. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 27(3), 832–837.

-

Parzen, E. (1962). On estimation of a probability density function and mode. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 33(3), 1065–1076.

-

Jones, M. C., Marron, J. S., & Sheather, S. J. (1996). A brief survey of bandwidth selection for density estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 91(433), 401–407.

-

Loader, C. (1999). Local Regression and Likelihood. Springer.

-

Bowman, A. W., & Azzalini, A. (1997). Applied Smoothing Techniques for Data Analysis: The Kernel Approach with S-Plus Illustrations. Oxford University Press.

Note: This article uses technical terms like bandwidth, kernel, bias-variance tradeoff, multimodality, and density estimation. For definitions, check out the Key Terms & Glossary page.