Day 8 — Adjusted Boxplot & Medcouple

Taming skewed distributions without crying wolf on legitimate extremes.

Note: This article uses technical terms and abbreviations. For definitions, check out the Key Terms & Glossary page.

Introduction

Regular boxplots assume symmetric data, so a long tail looks suspicious. Real-world datasets—salaries, housing prices, reaction times—are often skewed. The adjusted boxplot fixes this by combining Tukey-style fences with the medcouple, a robust skewness statistic.

TL;DR:

- Medcouple measures skewness on a scale from −1 → +1.

- Adjusted fences use exponential factors so the long tail gets extra space.

- Positively skewed data widens the upper fence and tightens the lower fence (and vice versa).

- Use adjusted boxplots when histograms look lopsided or domain knowledge says “long tail is normal”.

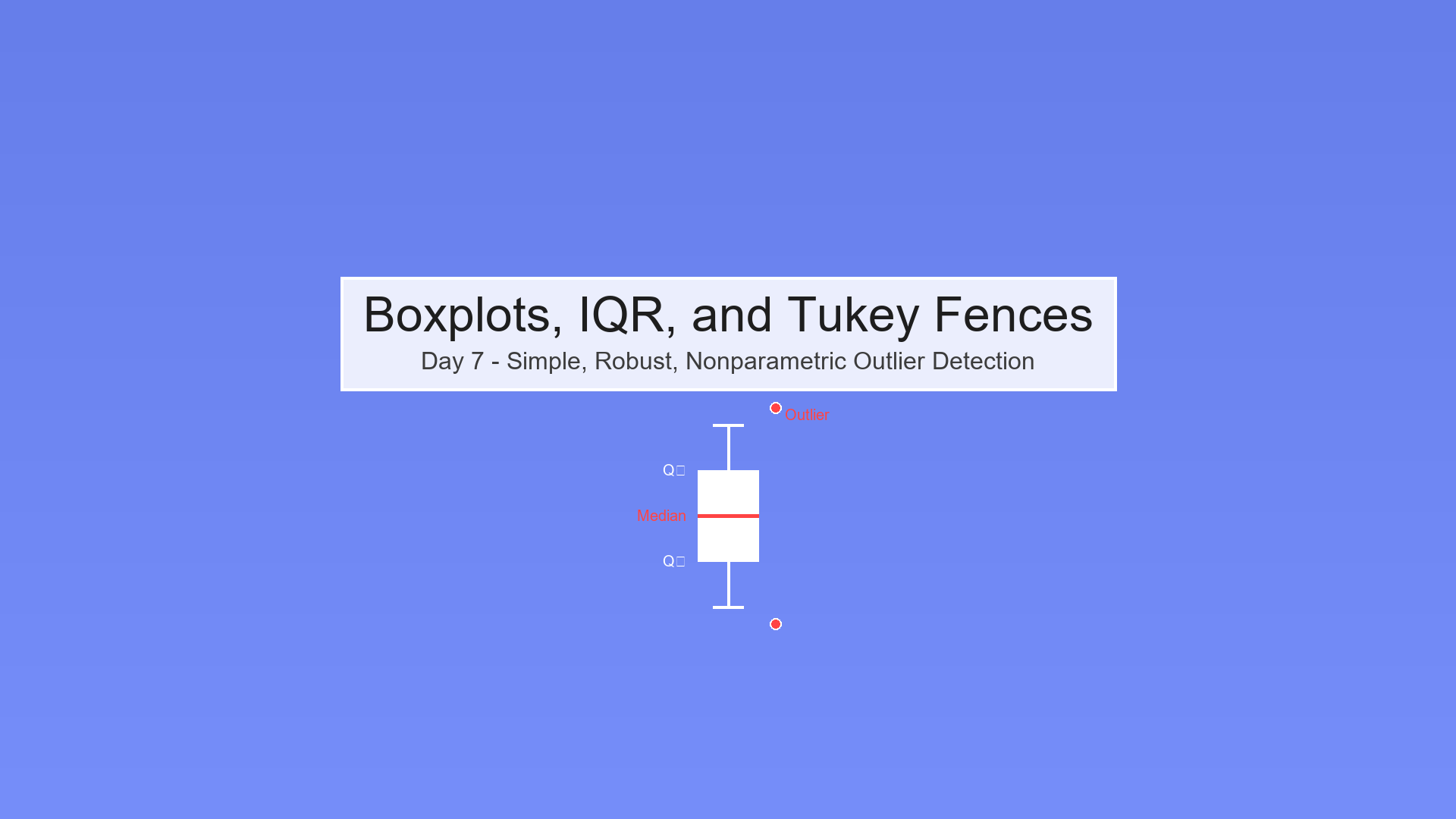

The Problem with Regular Boxplots

Imagine company salaries: most lie between ₹40k–₹80k, yet one executive earns ₹1600k. A traditional boxplot calls that an outlier because it places equal weight on both tails. The result: normal tail behavior is mislabelled as noise.

Why symmetric fences fail

- Traditional fences:

Lower = Q₁ − 1.5 × [IQR](/key)andUpper = Q₃ + 1.5 × IQR - Works brilliantly when the distribution is balanced.

- Breaks when a tail is naturally long—think incomes, clicks, insurance claims.

Regular boxplots think “extreme on either side” is equally likely; skewed data disagrees.

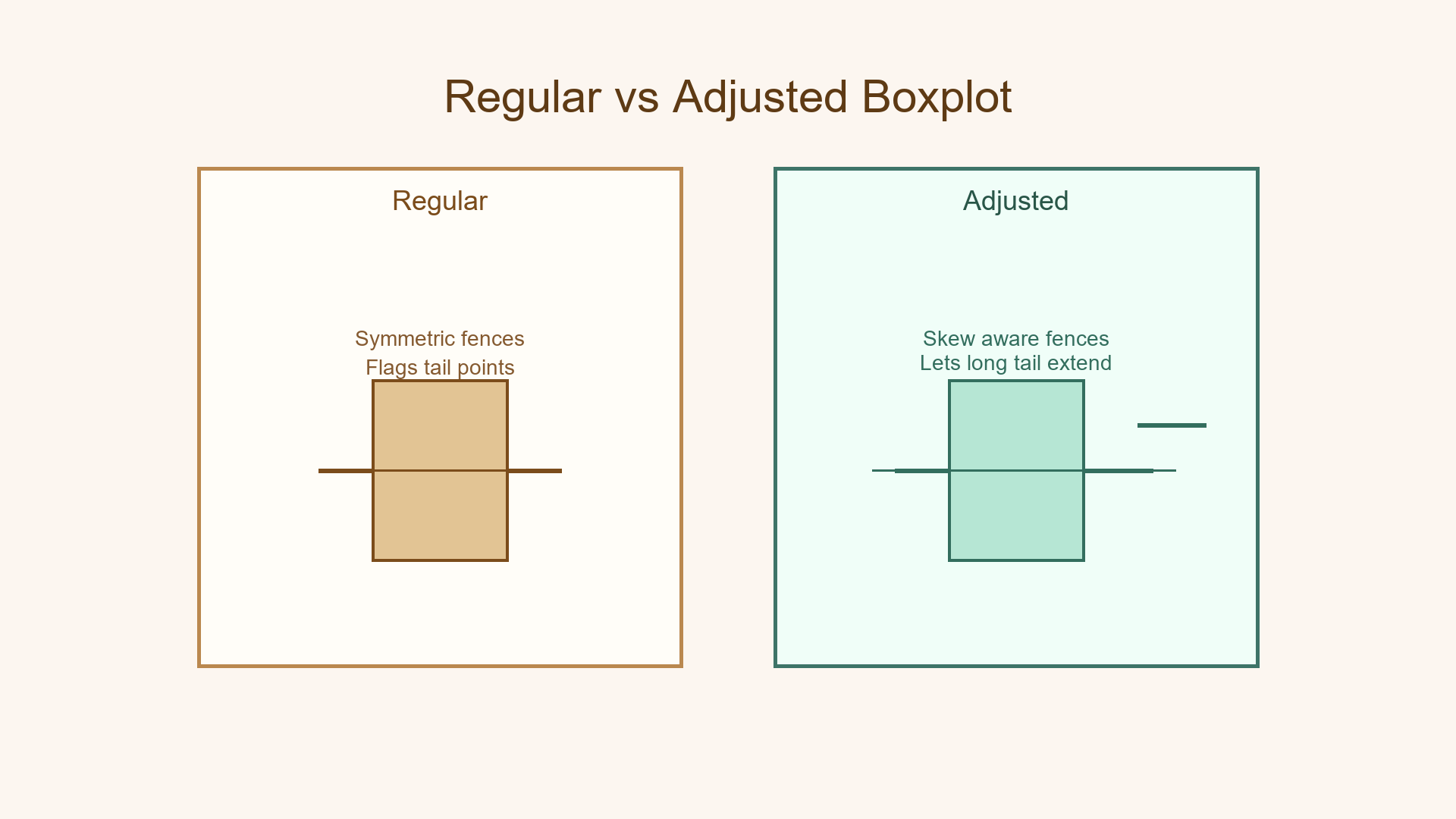

Enter the Adjusted Boxplot

The adjusted boxplot tweaks Tukey’s fences with an exponential factor driven by the medcouple. More skew means more asymmetry in the allowable range.

Smart guard analogy

- Regular guard: “Tall or short? Either way you look suspicious.”

- Adjusted guard: “Most folks are tall today; short people stand out more than tall ones.”

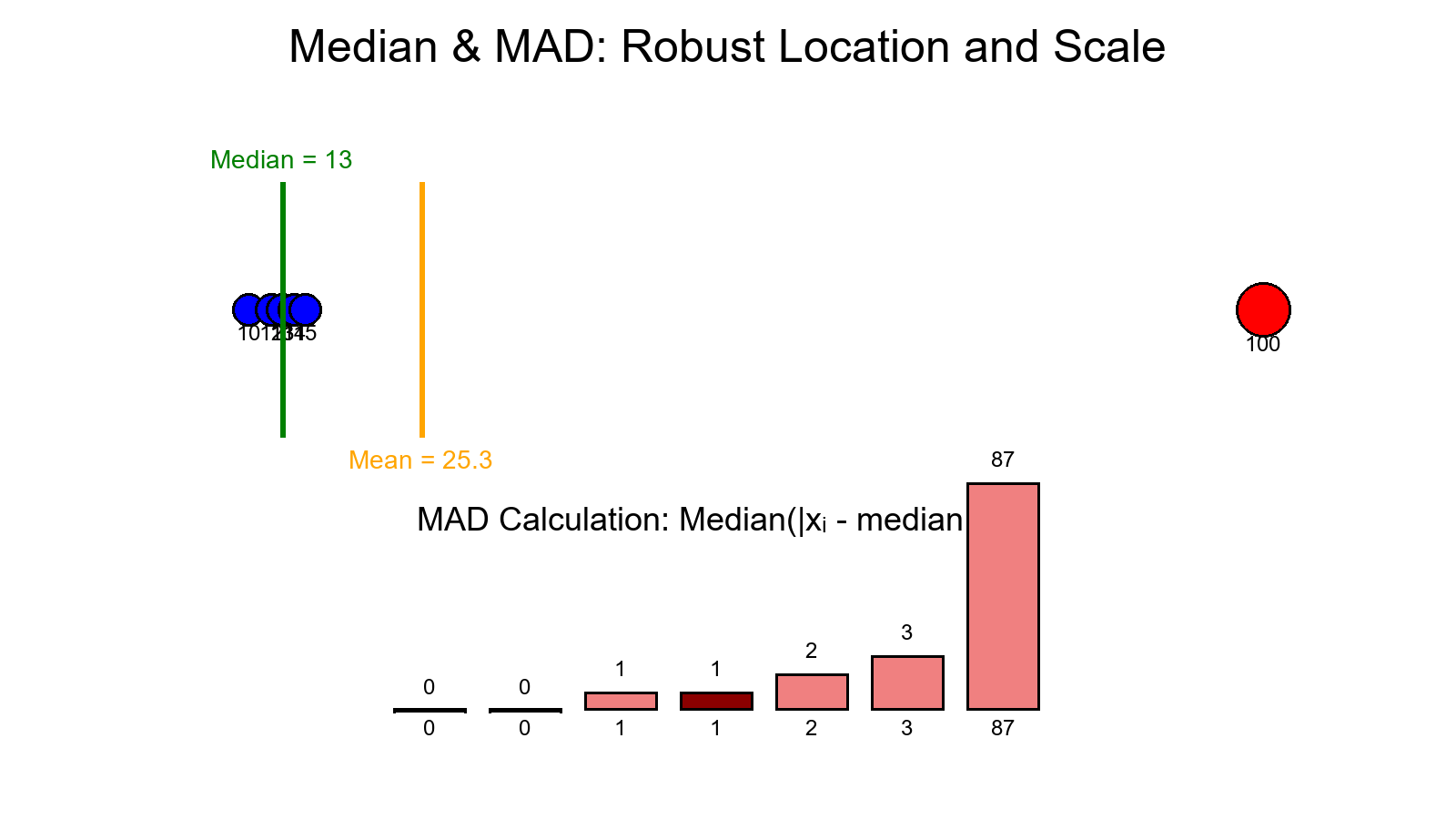

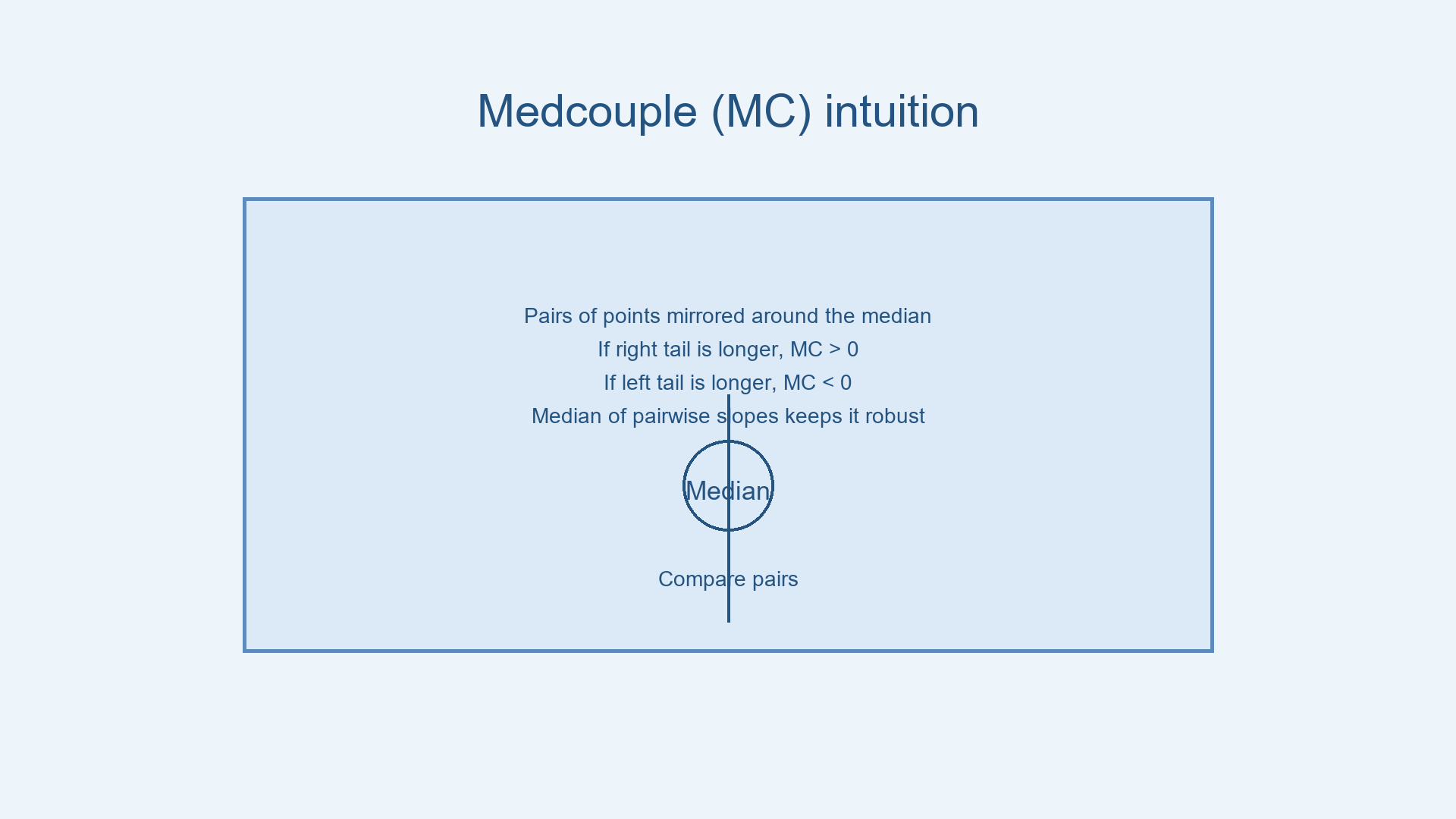

Meet the Medcouple (MC)

The medcouple is a robust skewness statistic that compares symmetric pairs around the median. It ignores extreme values and captures how one tail spreads relative to the other.

MC ≈ 0→ roughly symmetric.MC > 0→ positively skewed (long right tail).MC < 0→ negatively skewed (long left tail).

MC = median of h(xᵢ, x)

where h(xᵢ, x) = ((x - median) - (median - xᵢ)) / (x - xᵢ)

Robust means the statistic resists the influence of single extreme values—perfect for skewed data.

How the Adjusted Fences Work

Traditional fences use a fixed multiplier. Adjusted fences multiply 1.5 × IQR by an exponential function of the medcouple:

Lower fence = Q₁ − 1.5 × exp(−3.5 × MC) × [IQR](/key)

Upper fence = Q₃ + 1.5 × exp(+4.0 × MC) × [IQR](/key)

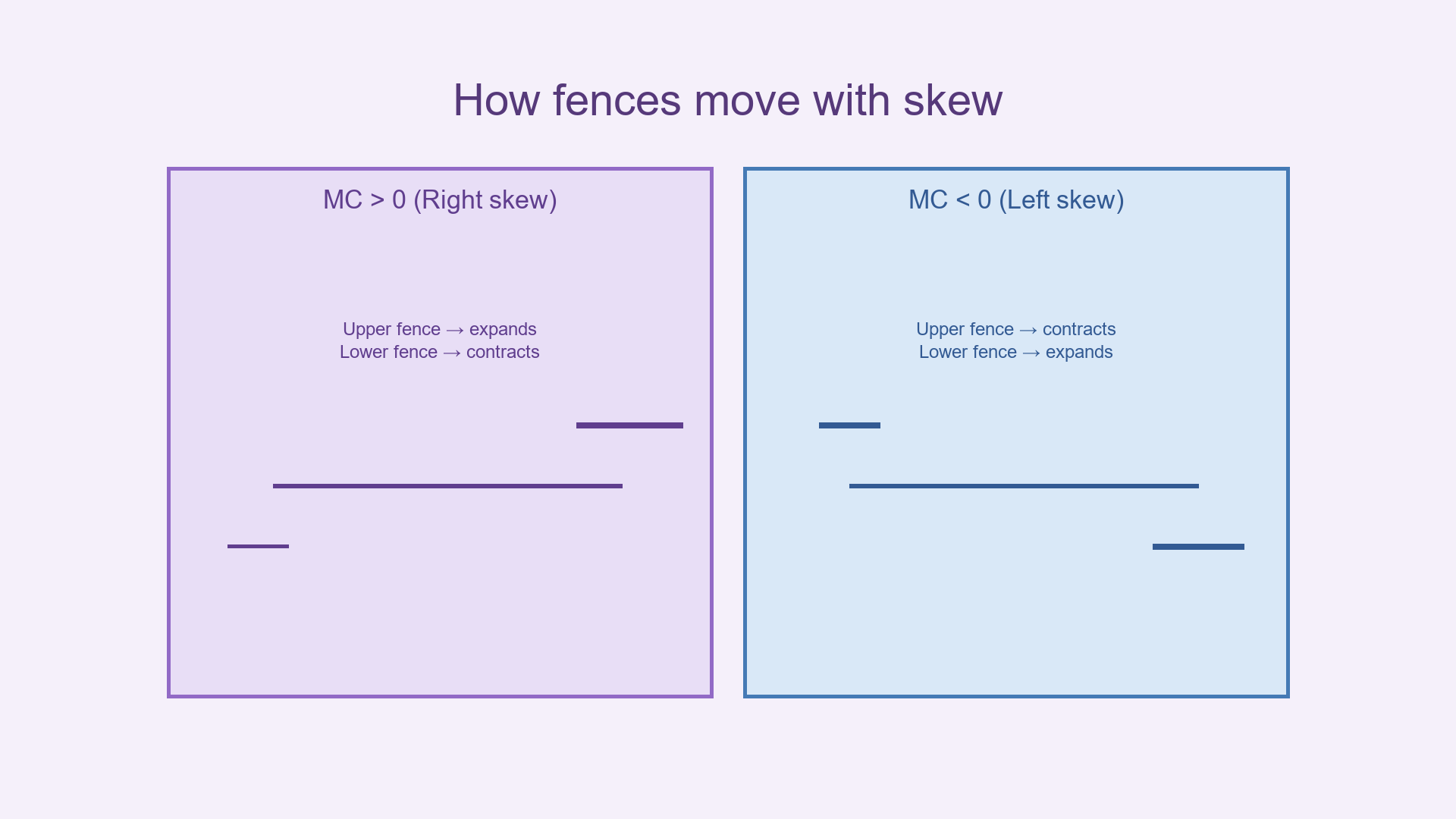

- Positive MC (right skew):

exp(+4.0 × MC)explodes, stretching the upper fence;exp(−3.5 × MC)shrinks, tightening the lower fence. - Negative MC (left skew): the behavior flips—lower fence loosens, upper fence tightens.

Worked Example — House Prices

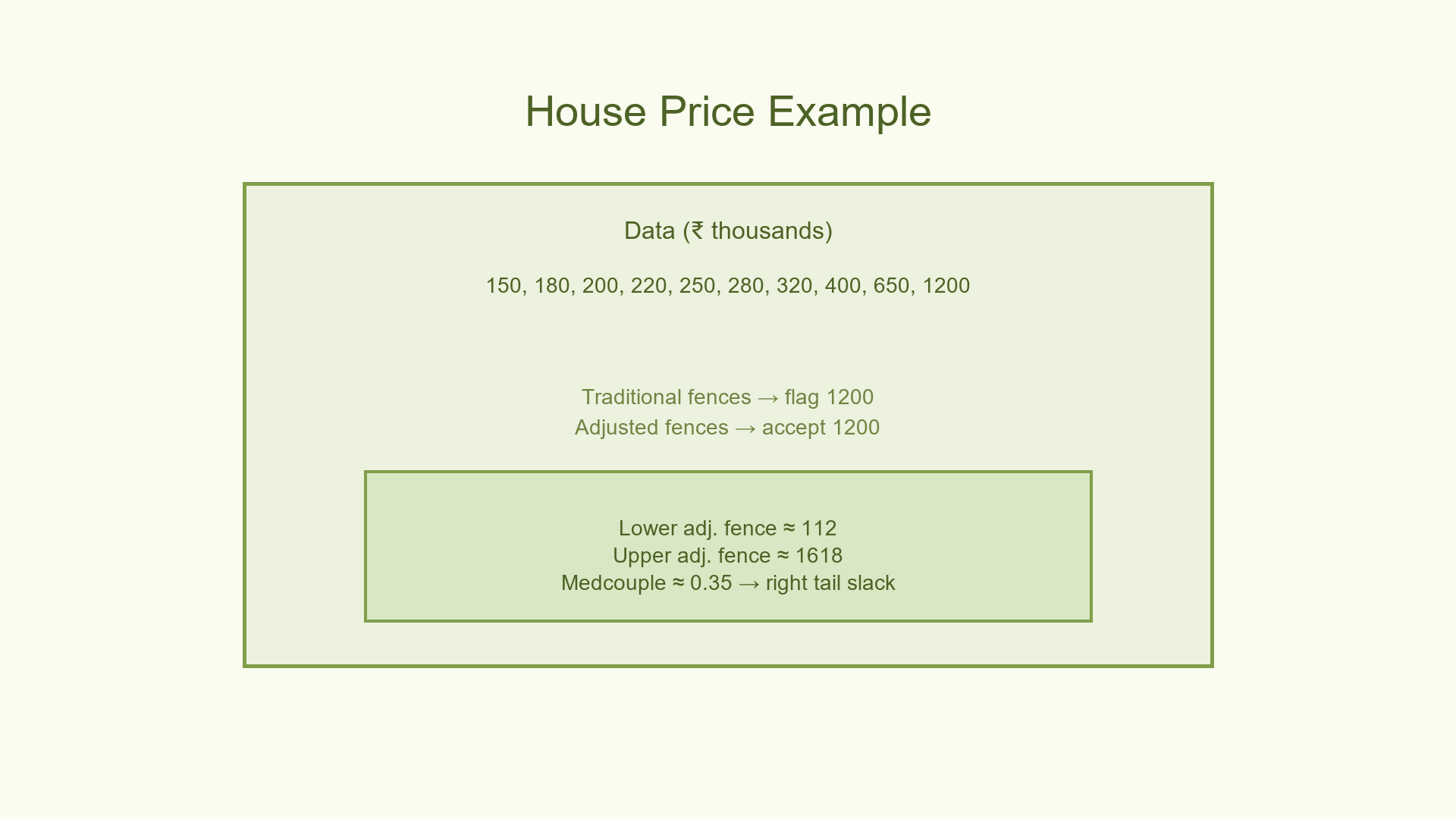

Dataset (₹ in thousands): [150, 180, 200, 220, 250, 280, 320, 400, 650, 1200]

[Q₁](/key) = 200, [Q₂](/key) = 265, [Q₃](/key) = 400

[IQR](/key) = 200

Medcouple ≈ 0.35 (right skew)

Traditional fences

Lower = 200 − 1.5 × 200 = −100

Upper = 400 + 1.5 × 200 = 700 → flags 1200 as an outlier

Adjusted fences

Lower = 200 − 1.5 × exp(−3.5 × 0.35) × 200 ≈ 112

Upper = 400 + 1.5 × exp(4.0 × 0.35) × 200 ≈ 1618

No outliers detected — the long right tail is normal for property values.

Pseudocode Implementation

Show code (10 lines)

def adjusted_boxplot_outliers(data):

Q1, Q3 = compute_quartiles(data)

IQR = Q3 - Q1

MC = compute_medcouple(data)

lower = Q1 - 1.5 * math.exp(-3.5 * MC) * IQR

upper = Q3 + 1.5 * math.exp(4.0 * MC) * IQR

return [x for x in data if x < lower or x > upper]

Tools like

adjusted_boxplot_outliersin our toolkit automate the math while you focus on interpretation.

When to Switch Boxplots

Use adjusted boxplots when:

- Histograms or density plots reveal skewness.

- Domain knowledge screams “long tail is normal” (salaries, prices, insurance claims).

- Traditional boxplots call too many valid values outliers.

Stick with regular boxplots when:

- Data is roughly symmetric or sample size is tiny (<20).

- You need a quick-and-dirty check for any extreme value.

Takeaway

- The medcouple captures skewness without being tricked by outliers.

- Adjusted boxplots expand and contract fences intelligently.

- Long tails stop masquerading as anomalies; true anomalies still pop.

Coming Up Next

Day 9 — Local Outlier Factor (LOF) explores density-based detection so you can catch anomalies hiding in neighborhoods.

References

- Annick Brys, Mia Hubert, and Peter Rousseeuw (2004). “A Robust Measure of Skewness.” Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics.

- Rousseeuw, P. J., & Hubert, M. (2011). “Robust Statistics for Outlier Detection.” Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery.

- Hubert, M., Vandervieren, E. (2008). “An Adjusted Boxplot for Skewed Distributions.” Computational Statistics & Data Analysis.

You Made It — Day 8

Thanks for sticking with the journey! Every day adds another robust tool to your kit.

** In one line:** Adjusted boxplots plus the medcouple let you respect skewed data while still catching the truly weird points.